— Animism as the Operating System of Japanese Culture

Long before written doctrine or centralized belief systems arrived in the Japanese archipelago,

there already existed a quiet but persistent way of relating to the world.

Not a religion in the strict sense.

Not a philosophy articulated in words.

But a mode of perception—a habit of seeing things not merely as objects,

but as vessels capable of holding something more.

In this essay, I refer to that underlying mode as “Animism OS.”

By “OS,” I do not mean belief or faith,

but a foundational layer—

an operating system that shapes how people intuitively interact with material forms,

technology, and culture.

Dogu: Characters Before Characters Existed

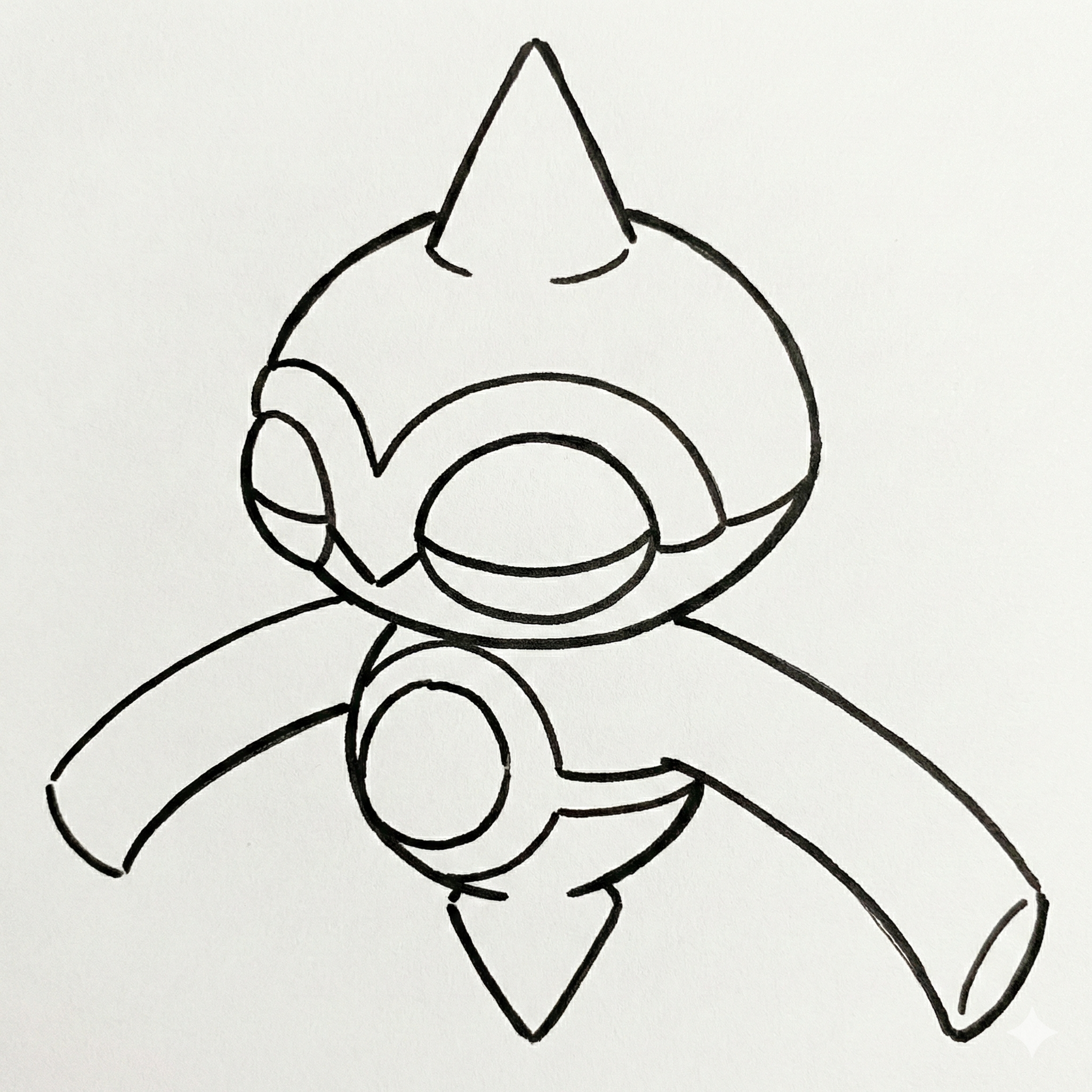

Jomon-era dogu figurines are often described as primitive or poorly proportioned human representations.

But this interpretation misses the point.

Dogu were not attempts at realism.

They were functional forms.

Their exaggerated eyes, distorted bodies, and non-human proportions

were not failures of technique,

but deliberate designs meant to activate something—

healing, protection, fertility, or spiritual mediation.

In other words, dogu were not images of humans.

They were interfaces between humans and invisible forces.

From Magic to “Moe”: A Shift in Function, Not Structure

The function of these forms has changed over time.

What once aimed at physical or ritual efficacy

now tends toward emotional and psychological effects—

comfort, attachment, affection, what modern Japanese culture calls moe.

Yet the underlying structure remains the same:

- A material object is given form

- Meaning, emotion, or presence is projected into it

- The object mediates the relationship between person and world

The type of power has shifted,

but the operating system has not.

Material + Spirit as System Design

This logic appears with striking clarity in modern Japanese games and characters.

Some designs explicitly combine material attributes (earth, clay, weight)

with spiritual or psychic attributes.

This is not merely storytelling.

It is worldview implemented as system design.

Animism here is not explained—

it is encoded.

Grotesque and Cute: Coexisting Without Resolution

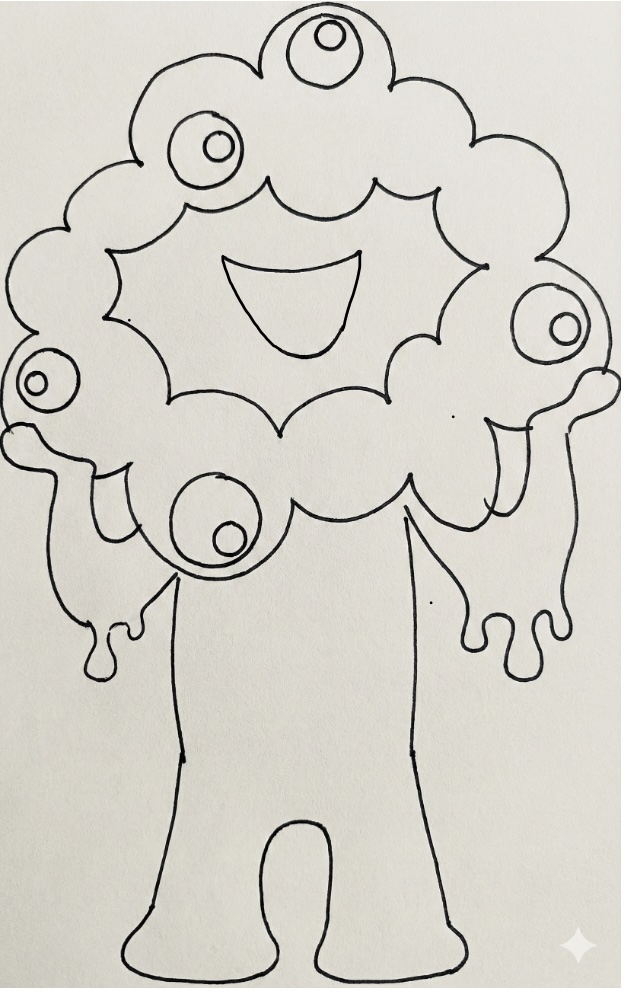

Another distinctive feature of this cultural OS

is the coexistence of the grotesque and the cute.

Dogu are unsettling and endearing at the same time.

So are many modern characters, mascots, and creatures.

Rather than resolving ambiguity,

Japanese visual culture often preserves it.

This reflects a worldview that does not insist on clean separation—

between fear and affection,

between object and subject,

between the living and the non-living.

Modern Local Spirits

In contemporary Japan, local mascots often function

less like marketing tools

and more like modern placeholders for place-based spirits.

They give “faces” to regions,

invite touch and attachment,

and are carried home as objects of connection.

The ritual has changed.

The OS has not.

Why This Matters

Looking back, I realize that even in my own work,

this OS quietly operates.

Moments that should be “just tasks”

sometimes feel charged with meaning.

Small anomalies draw attention.

Insignificant details feel alive.

This tendency—to sense something more where none is required—

is not necessarily rational.

But it may be deeply cultural.

Animism OS is not something Japan believes in.

It is something Japan runs on.

And once you notice it,

you begin to see it everywhere—

from ancient clay figures

to modern characters

to the quiet moments in everyday work

that refuse to remain mere objects.