It Wove Them — and a Culture Emerged

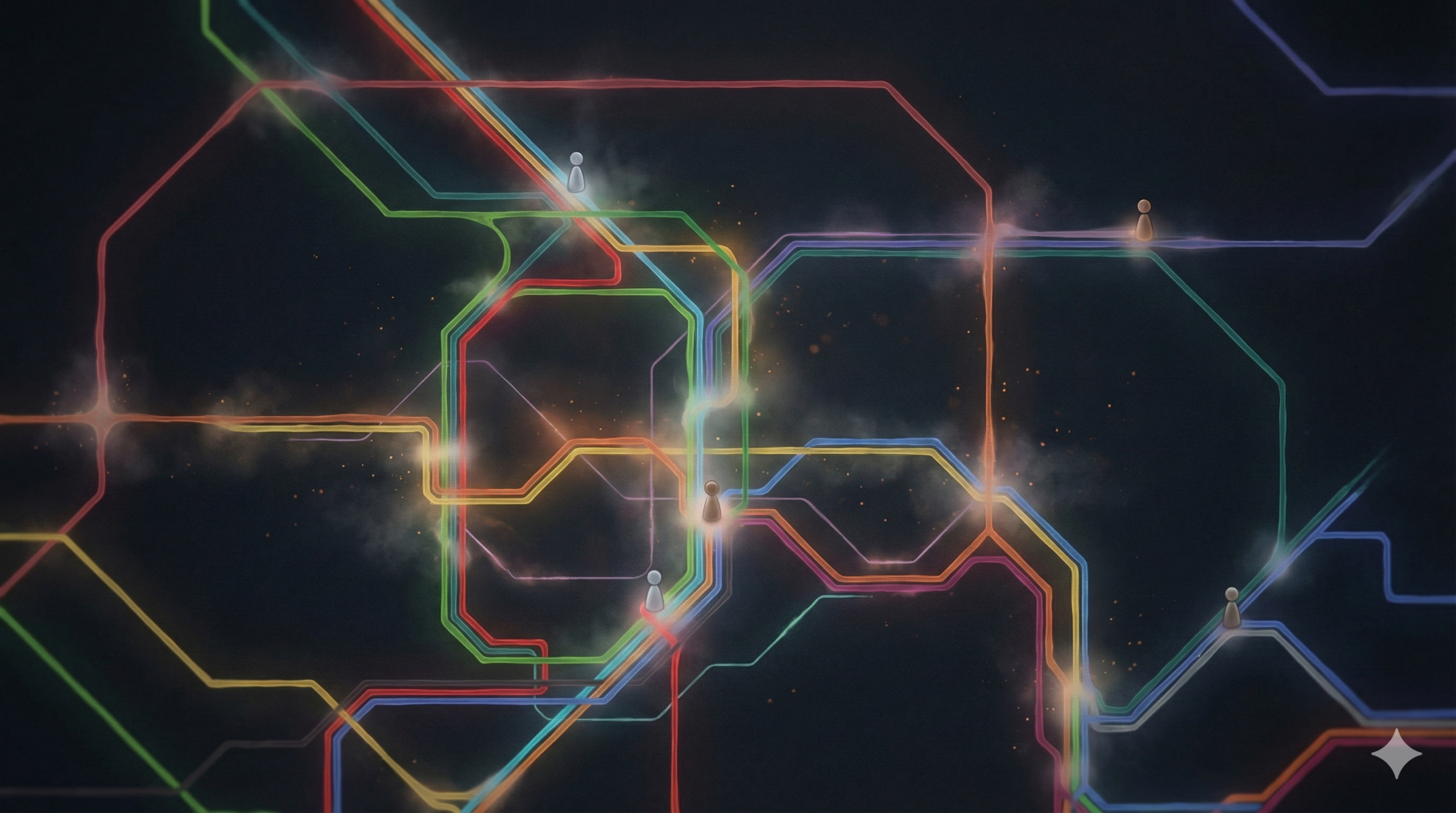

When people outside Japan look at a Tokyo railway map,

their first reaction is often the same:

“Why is it so complex?”

Lines overlap, intersect, diverge, reconnect.

Multiple operators share tracks.

Routes feel less like straight lines and more like a tangled web.

To many, it looks chaotic.

But to those who live in Japan, this complexity is not an exception.

It is daily life.

I believe this structure — this spiderweb of railways — did more than move people.

It shaped how people live, adapt, and even how culture itself diversified.

Railways as a Spiderweb, Not a Spine

In many countries, railways follow a “spine” logic:

a main line connecting cities point to point.

Japan took a different path.

Because of its geography — mountainous terrain and limited habitable land —

population and industry concentrated intensely in flat urban areas.

Post-war reconstruction and rapid economic growth caused cities to expand simultaneously, not sequentially.

One line was never enough.

Railways had to be dense, overlapping, redundant.

They had to absorb enormous daily flows of people — reliably, repeatedly, every morning and evening.

The result was not a hierarchy, but a network.

Not a backbone, but a web.

From Farmers to Urban Life

After World War II, millions of people left rural areas for cities.

Many were former farmers who became factory workers or office employees.

They moved into newly built apartment complexes — what Japan calls danchi.

These apartments were small.

But they had running water, electricity, gas, bathrooms, televisions, refrigerators.

At the time, this was modernity itself.

What made this lifestyle possible was the railway.

Railways were not just transportation.

They were life-support systems — carrying workers, routines, schedules, and expectations.

This everyday dependence planted the seeds for something more.

Railways Became Ordinary — and That Changed Everything

In Japan, trains were not special events.

They were not reserved for travel or leisure.

They were used every day.

When infrastructure becomes ordinary, people stop admiring it —

and start interacting with it.

And when a system becomes too large and too complex to fully grasp,

people don’t stop engaging with it.

They choose how to engage.

This is where Japanese railway culture begins to branch.

Railways Are Not Just Loved — They Are Used in Different Ways

In Japan, railway enthusiasts are often called tetsu (from densha tetsudō, railway).

But tetsu are not simply “train lovers.”

They are people who choose a specific way to relate to the system.

For example:

- Riding-through tetsu

- Waiting-and-photographing tetsu

- Vehicle-detail tetsu

- Schedule-decoding tetsu

- Miniature-world-building tetsu

- Memory-collecting tetsu

- Drinking-and-drifting tetsu

These are not categories of taste.

They are categories of action.

Riding-through tetsu

They ride from the first station to the last.

Local trains, express trains — it doesn’t matter.

They trace the network with their own bodies.

Waiting-and-photographing tetsu

They wait for hours for a single moment.

A specific train, a specific light, a specific second.

Vehicle-detail tetsu

They care about models, manufacturing years, modifications.

For them, each train is an industrial artifact.

Schedule-decoding tetsu

They read timetables like puzzles.

Why this buffer time? Why this connection?

They see railways as systems of constraints and logic.

Miniature-world-building tetsu

They build entire railway worlds in small scale.

Tracks, towns, timetables — all reconstructed by hand.

Memory-collecting tetsu

Tickets, signs, station stamps, destination boards.

They preserve time as objects.

Drinking-and-drifting tetsu

They ride slowly, drink locally, arrive eventually.

For them, trains are not destinations but intervals.

This Diversity Was Inevitable

This diversity did not emerge because Japanese people love trains “too much.”

It emerged because the system itself was too complex to consume as a whole.

When a structure becomes unreadable in its entirety,

people select perspectives.

They don’t ask, “Do I like this?”

They ask, “Where do I enter?”

Perspective becomes culture.

Adapting to the Hard, While Playing Within It

There is a broader Japanese mindset behind this.

Schedules are strict.

Rules are clear.

Infrastructure is massive and non-negotiable.

Rather than resisting it, people adapt to it —

and then quietly play within its constraints.

Obedience does not eliminate creativity.

It redirects it.

By following the system, people find room to reinterpret it.

By accepting the structure, they find freedom inside it.

Pop Culture Lit the Spark — Infrastructure Kept the Fire Burning

Anime, literature, film, and music often feature trains in Japan.

But railways did not become cultural symbols because of pop culture.

Pop culture arrived after the infrastructure.

The spiderweb already existed.

Daily life already flowed through it.

Stories simply attached themselves to what was already there.

Pop culture lit the spark.

The railway network — and the people living within it — supplied the fuel.

In Closing

Japan did not build railways only for efficiency.

In doing so, it unintentionally created:

- a daily rhythm of movement,

- a networked urban life,

- and countless ways to engage with a single structure.

The railway web did not trap people.

People entered it — willingly, creatively, selectively.

“Tetsu” are not consumers of trains.

They are readers of structure.

And in that reading,

a uniquely Japanese culture emerged.